This article is about my first year of teaching art at a high school on Chicago’s South Side. It was originally written in 2022. Since the time of this writing, the school has experienced improvements in attendance and literacy, two of my students lost their lives, the boys basketball team earned two state basketball titles, and the school still deals with dramatic budget cuts and high teacher turnover every year.

On a normal Monday morning at Wendell Phillips Academy High School in Bronzeville, Chicago, the small gestures matter most. A colleague may greet me with “grand rising,” a conscious choice to resist associating the start of our day with the mourning of “good morning”. Security guards play throwback jams at the metal detector entry, an upbeat antidote to the routine security checks. A second metal detector greets students entering the auditorium, underscoring the tension between safety and surveillance embedded in our daily rituals. By the time I unlock my classroom door at 8:00 am, only one student waits outside—a stark contrast to the thirty names on my roster.

Attendance hovers around 60% schoolwide, but in first period it’s even lower, a reality shaped by transportation challenges and instability. Soon, two more students enter, one eats quietly, the other rests his head; both immensely talented artists whose personal circumstances often overshadow their academic potential. A former student bounces in for a quick visit, and names the classroom plants—Blossom, Sage, Aurora, Rapunzel. Football players burst into an impromptu acapella rendition of Kirk Franklin’s “I Smile”—a spontaneous, joyful resistance to a morning constrained by rigid scheduling.

These are not the conditions most people imagine when they think about the future of education. But in a building shaped by abandonment, I began to understand that the future of learning—if it’s worth building—might depend on something else entirely. When traditional metrics fail to capture what students are actually navigating, creative thinking isn’t extra—it’s essential. My job isn’t to train artists. It is to help students make meaning, assert agency, and begin again in spite of everything. If we are serious about reimagining education, we need to recognize creativity as its own kind of literacy—one especially vital in places where systems have long since stopped working. That future won’t be built from new policies alone. It will begin in the classrooms where students are trusted to make something real.

From the outside, Chicago’s South Side is often framed through a narrow lens: violence, poverty, neglect. These headlines flatten a place alive with culture, care, and resilience. Phillips Academy, historically significant as Chicago’s first Black high school and alma mater of cultural icons like Herbie Hancock and Dinah Washington, stands as a testament to that complexity—a site of both historical pride and systemic neglect. As part of Chicago Public Schools—the third-largest district in the country—Phillips sits within a landscape shaped by racial segregation and resource disparity. While North Side selective-enrollment schools boast AP offerings and new science labs, many neighborhood schools on the South and West Sides face chronic underfunding, teacher shortages, and inconsistent leadership. These inequalities aren’t theoretical. They materialize daily as missing supplies, empty classrooms, and students trying to learn in survival mode.

The visual art class I teach isn’t a reprieve from these conditions. It is shaped by them. And yet, that’s precisely where something vital begins to emerge. When systems collapse, creativity can become not just expression—but infrastructure. Not an escape, but a means of rebuilding.

When I arrived at Phillips, the school hadn’t had a full-time art teacher in years. My predecessor lasted six weeks. There were no supplies, no working computers, no functioning sink. Average daily attendance hovered around 60%, and many of the students I inherited hadn’t received consistent art instruction since before the pandemic—and in many cases, longer.

Before Phillips, I had spent seven years teaching at the University of Iowa, where I worked with pre-service teachers, developed workshops grounded in creative thinking research, and won teaching awards. I knew how to run a classroom. At Iowa, I had studied how creative thinking skills can transform classrooms. I believed art education didn’t have to be about becoming an artist; it could be about learning how to think, improvise, and see differently.

When I interviewed for the position at Phillips, the principal was candid: “We’ve had trouble finding an art teacher who stays. We don’t have supplies. The kids need a space to explore their talents.” I didn’t know what to expect, so I vacuumed and cleaned the dusty old classroom they assigned me. I discovered 70 year old newspaper clippings in an old ceramic crock. As I lit palo santo and wiped down the shelves, I whispered Sanskrit mantras into the space, asking it to hold something truly sacred.

I started teaching the Tuesday after the President’s Day holiday: 2/22/2022. I walked into a dark building. I asked the other teachers, “Is this normal?” They laughed and said, “No, the power is out. Welcome to Phillips.” Students were sent to a nearby church until the power came back on. The second day, I received a donation of Prismacolor pencils, paint brushes, tubes of acrylic paint, oil pastels—barely-used supplies bearing the names of kids from the suburbs—Hailey, Kaylee, Bailey, Braley, Braden. I started class with a quote from adrienne maree brown about the imagination battle. Everyone wore masks. I came in ready to build a sanctuary, to teach creative risk-taking and vision. What I found instead was a daily negotiation with chaos.

The formal lessons I had planned—lectures, critiques, reflective conversations—were drowned out by noise, by hunger, by chronic absence, by a level of dysregulation I hadn’t witnessed even during the pandemic. Students came to class late, high, overstimulated, exhausted, angry, brilliant. Many couldn’t sit still long enough to hear directions. They could not, would not, sit through a slide deck. Many could barely read the whiteboard instructions I posted. Others disappeared for weeks and reappeared with no explanation. Many were still recovering from two years of pandemic learning loss, isolation, and unacknowledged trauma. I tried exit tickets, unit reflections, writing prompts. Most students didn’t respond. When they did, their spelling and grammar made it clear: this wasn’t disengagement. It was illiteracy.

CPS internal data later confirmed what I had begun to suspect. Over 90% of Phillips students tested far below grade level in reading. Fewer than five students in the entire building scored at or above benchmark. This was not a failure of effort. It was a systemic abandonment, worsened by years of pandemic disruption, substitute shortages, and deep-rooted inequities in city funding structures. For two years during quarantine, students disappeared from classrooms. The district let them pass anyway. By the time I met them, many hadn’t had a consistent teacher since ninth grade or before.

I pivoted my approach. Not because I had a radical plan, but because survival demanded it. I stopped trying to deliver formal instruction. I stopped expecting the whole class to move in unison. Instead, I learned each student’s name. I figured out who liked shading, who wanted to draw their dreams, who needed to put their head down for five minutes before starting anything. I gave them three kinds of prompts and let them choose. I asked them to finish one big thing every two weeks. I checked in with each student individually, every day, wherever they were in their process. I hung finished work in the hallway. Before long, the hallway was filled from floor to ceiling with artwork.

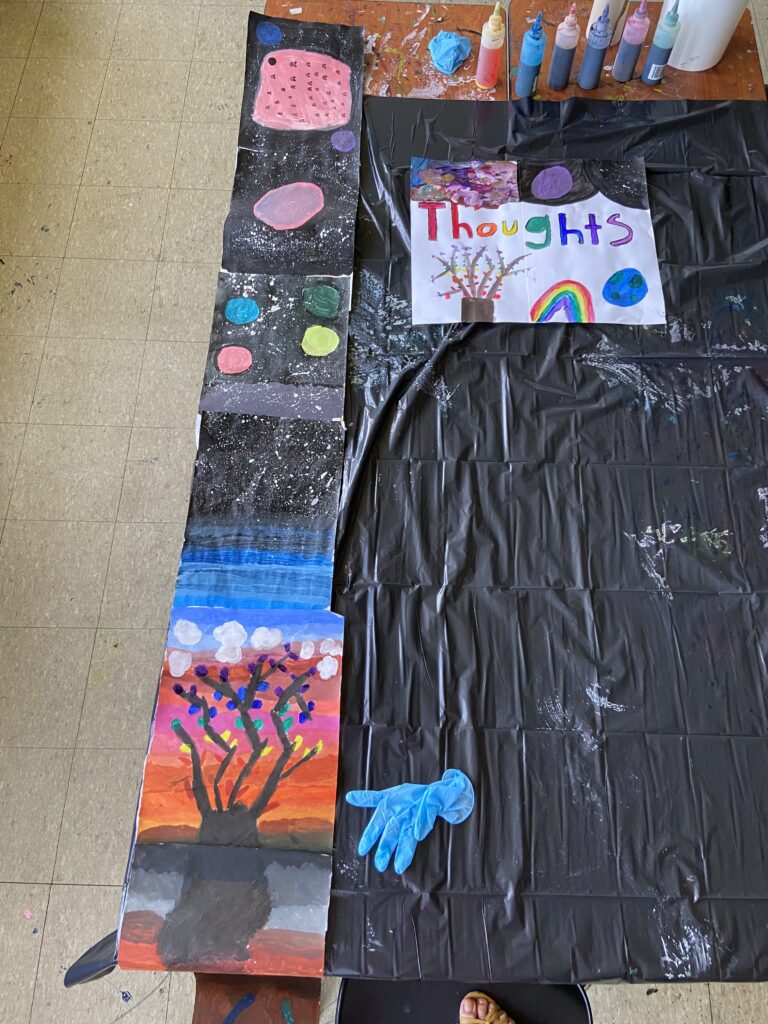

I had dozens of little conferences throughout each day; it was tiring, but it was dynamic and interesting. Most of all, the ideas for the work came from the students. They would just start painting or drawing, and we would talk about what they liked about it or what they were most interested in and go from there. Some would come to me and say, “I want to work on shading or drawing something realistic” and I would have pictures printed for them to work from (even though I was not given a printer for my room) and give them new tips and skills to work on when they were ready. One young lady made a series of paintings in which she exacted revenge on her toxic boyfriend, another made a series of paintings where she imagined what is above the trees? And above that? And above that? And what lies below? And below that? And below that? Any prompt or assignment I would have given would have paled in comparison to what the students came up with on their own volition. One young lady discovered painterly vibrational color layering by accident and painted pink mountain ranges with the letters of her name inscribed within each peak. Another young lady painted everything blue. For some reason, everything she touched came out bluer than when other kids used the same hue. She always wore blue braids in her hair. One young man made a gorgeous multi-layered pastel image of galaxies and comets, then vanished from my roster. I never saw him again.

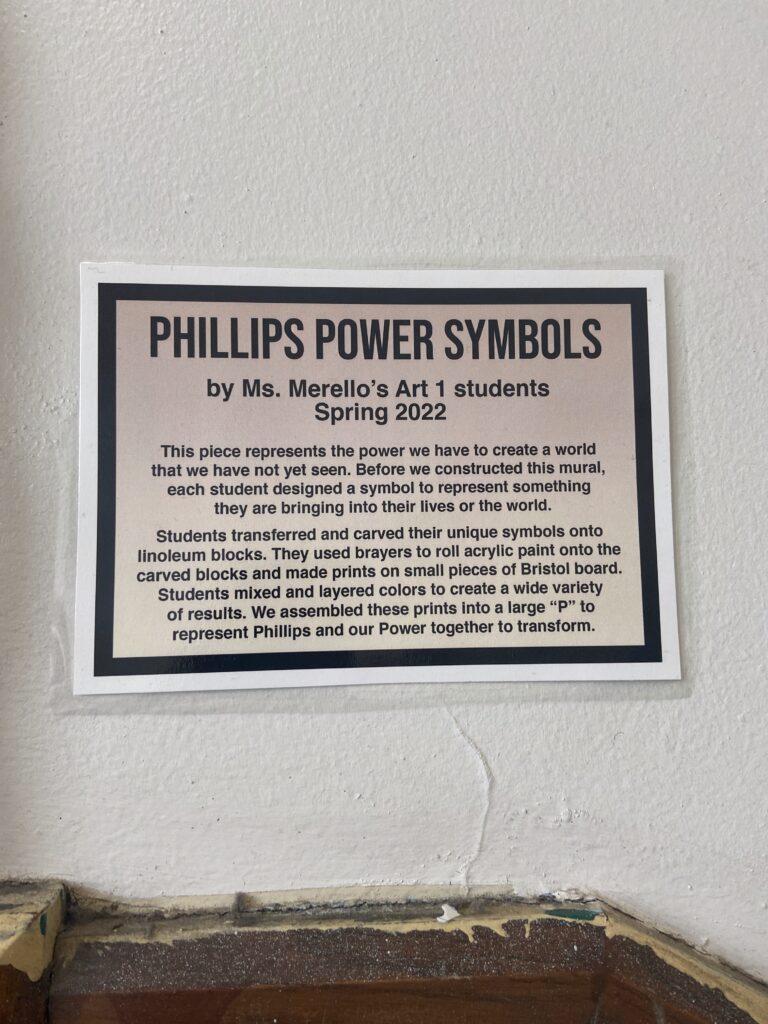

Eventually, I started breaking projects into steps, creating units that deepened ideas over time. My first formal unit was called “Power Symbols.” Students chose something they wanted to call into their lives—peace, strength, money, clarity—and designed a symbol from the letters of their word. They carved these symbols into linoleum blocks and printed them in our school colors. We combined the prints into a giant tapestry in the stairwell, fading from midnight blue to a pale “P” in the center: Phillips. Power. Positivity. “Pushin’ P”, as the kids said. When I brought my class to see it installed, one student said, “Everyone designed a symbol that means something to them. Seeing all of that together, you can feel it.” I could feel it, too.

This wasn’t just teaching—it was resistance. In a system that expects compliance, I chose flexibility. In a school dismissed as failing, I centered dignity. In a city where South Side schools are too often seen as problems to be fixed, I bore witness to the quiet brilliance of students who, given space, will find a way to say something true.

But the truth is, much of the time, I felt like I was underwater. Managing the space was its own act of endurance. I had 130 students and no aide. Many had undiagnosed or unsupported learning disabilities. My classroom had two doors—students snuck in the back or left unnoticed. Others skipped gym to vape in my back room. I hauled five-gallon paint buckets to the bathroom every day because the sink didn’t work. We had no soap. I brought my own. I wore noise-canceling earplugs and played 90s R&B to soothe the room. Students often came just to be in the space. Other teachers and administrators told me I must be doing something right—kids seemed to like me. Whenever a guest adult entered my classroom, they always commented about the peaceful vibe.

As I adjusted, I learned to protect the sanctuary I was building. I rearranged my schedule to include breaks. I created office hours during prep periods. I blocked the back door with filing cabinets. I stopped letting in extra students unless they had a pass. I tightened boundaries and saw trust grow stronger. I learned to say no. The more I protected the space, the more students respected it. To the outside world, this might look like improvisation, but make no mistake: this was pedagogy. Every choice I made was informed by creative thinking research, trauma-informed practice, and the realities of the environment I was in. I didn’t abandon rigor—I redefined it. In a setting where traditional academic measures were meaningless, I focused on process, persistence, and self-trust. I measured success by whether students could finish something, reflect on it, and see themselves differently as a result.

The resilience I witnessed wasn’t just individual—it was communal. Students helped each other find supplies. Helped each other walk through creative problem-solving challenges. They collaborated on group projects, shared feedback, celebrated breakthroughs, and protected each other’s work. They told me when something wasn’t working. They named the classroom plants. They made the space sacred alongside me.

Creative thinking is not extra, it’s a survival skill. In a world where AI reshapes jobs and screens fracture attention, students need more than content—they need consciousness. They need to understand their thoughts and choices as powerful. Visual art offers that. It allows students to see their thoughts in physical form. It rewards persistence, builds self-awareness, and—unlike traditional content delivery—can withstand chaos. It teaches flexibility, synthesis, and improvisation. It motivates students to finish something, even when it’s hard.

And yet, most educational reform never touches rooms like mine. Standardization was never built for students navigating survival. Compliance can’t measure what it takes to show up, to begin, to keep going. If we’re serious about reimagining education—especially in places long written off—we need to center what’s already working in the margins. We need to trust teachers to adapt in real time. We need to give students space to try something real. That doesn’t mean lowering expectations. It means shifting them—from performance to presence, from control to trust, from outcomes to process.

I don’t have a blueprint, but I’ve seen what becomes possible when students are met with care instead of scrutiny, when classrooms become studios for becoming. When we stop asking “How do we control the outcomes?” and start asking, “How can I help you trust yourself?”