Why do we teach art in schools? Is it to prepare students for careers? To beautify our hallways? Or is there something deeper at play—something about how we experience the world? Nearly a century ago, philosopher John Dewey posed these questions, and his answers are more relevant today than ever.

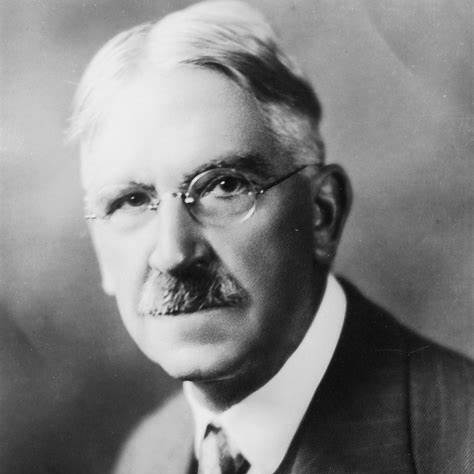

Dewey and Art as Experience

John Dewey, the education philosopher whose ideas shaped progressive education, published Art as Experience in 1934—more than three decades after founding the University of Chicago Lab School and writing School and Society. In Art as Experience, Dewey became the first education writer to examine the purpose and function of art education in schools beyond its vocational utility. He illuminated a unique dilemma: art learning within a capitalist system that values objectification, and within an administrative education system that reduces learning and experience to measurable outputs.

For Dewey, art’s value lies in the experience of making and engaging with it. Removing art from the actual process of creation distances both the maker and the observer from its transformative potential. He introduced the idea that art moves in a “temporal arc”—an experiential flow that lives beyond the moment of creation or the finished object. For educators and policymakers, this offers a powerful shift in perspective: from product to process.

Art, Capitalism, and Disconnection

Dewey also challenged the Western capitalist tendency to treat art as object, separate from the flow of daily life. In contrast to Indigenous and non-Western traditions where art, spirit, and life are intertwined, Western cultures compartmentalize art and spirituality. This separation paves the way for factory-style production and consumption.

Dewey puts it bluntly: “the nature of the problem is that of recovering the continuity of esthetic experience with the normal processes of living” (p. 9). Without that continuity, society elevates those who “use their minds without participation of the body and who act vicariously through control of the bodies and labor of others” (p. 21–22). Buying a product becomes a substitute for engaging in the creative act. This disconnection from process, Dewey warns, is deeply problematic.

The Role of Art Education

Dewey’s critique has direct implications for how we teach art. If we allow commodification to define art’s value, then art education risks becoming another cog in the machine—stripped of its vitality and reduced to technical skill-building or decorative output.

To resist this, Dewey calls for educational environments that facilitate open-ended, self-directed exploration. Meaningful understanding, he argues, can only arise when students engage in authentic, lived experience—not when they’re rushed toward standardization or assessment. Just as Western culture loses the depth of art when it objectifies it, schools lose the power of art education when they demand measurable products instead of fostering creative presence.

Why It Matters Now

In an era where creativity is touted as a 21st-century skill, Dewey’s work reminds us that true creativity begins in embodied, continuous experience. His vision urges educators, artists, and policymakers alike to shift the focus from outcomes to ongoing process—to honor the arc of learning that cannot be contained in a grade, product, or spreadsheet.

By recovering this continuity, we don’t just improve art education—we reconnect to something essential in human life: the capacity to experience, to participate, and to create meaning through presence.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York: Minton, Balch & Company.

© 2025 Andrea Merello. All rights reserved. Please do not reproduce this content without permission.